How ESG principles are reshaping the way companies are valued in the modern economy

Introduction to Evolution of ESG in Corporate Valuation

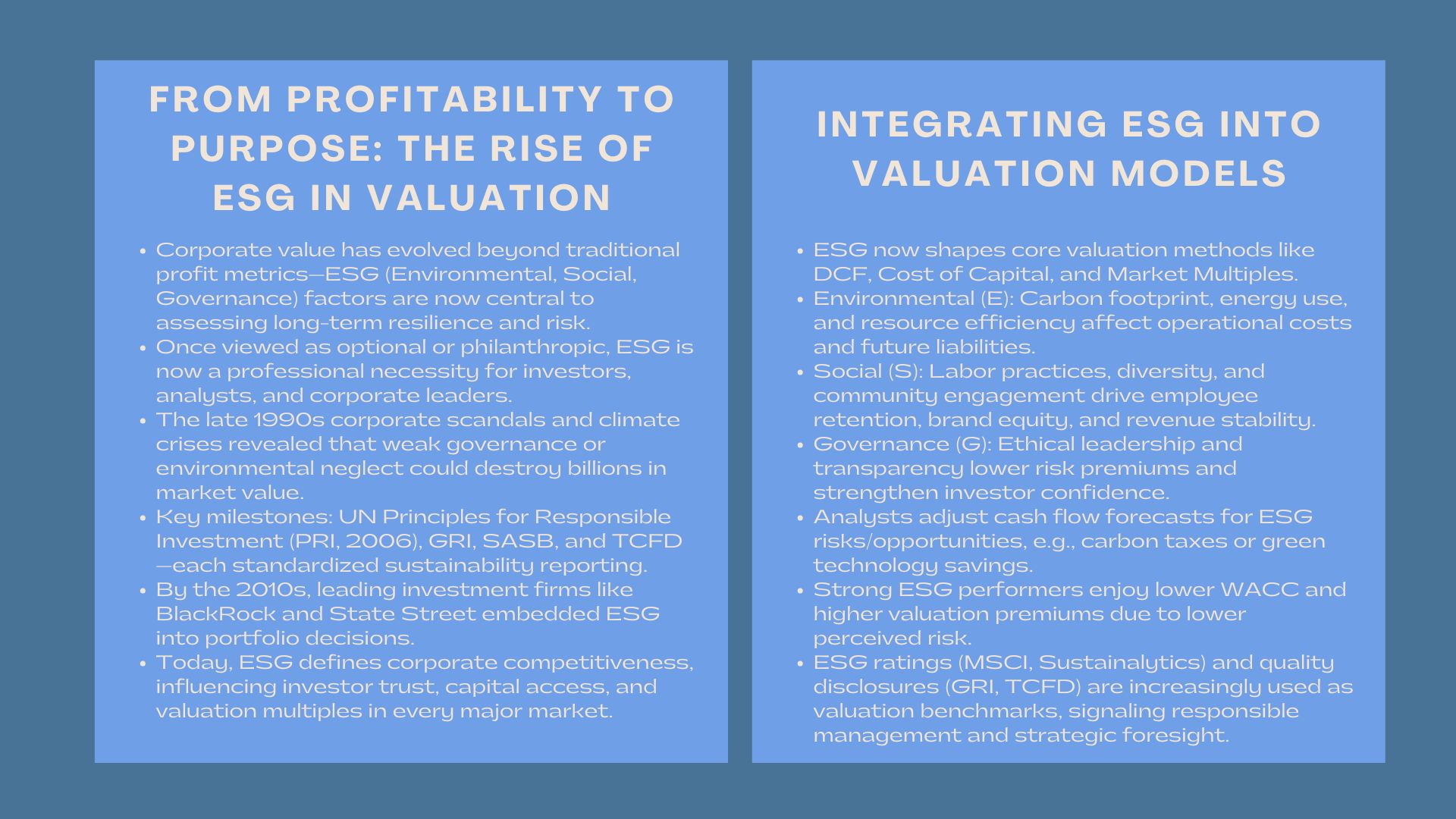

The paradigm of corporate value has grown well beyond profit margins and balance sheets in terms of breadth in the current globalized and sustainability-oriented world. Environmental, Social and Governance principles (ESG) which were seen as optional or philanthropic have become part of the analysis of long term viability and risk profile of a company. To investors, analysts and other financial industry professionals, understanding the way ESG is incorporated into valuation is no longer a specialized pursuit; it is a professional requirement.

The evolution of ESG principles in modern company valuations reflects a broader transformation in the business and investment landscape. As global markets grapple with issues like climate change, resource scarcity, and social accountability, traditional valuation methods have evolved to account for non-financial factors that can materially affect performance and reputation. This shift is especially important for those entering or advancing in corporate finance, sustainability consulting, or investment analysis—fields that increasingly demand fluency in both numbers and impact.

This article discusses the way in which ESG and sustainability concepts have evolved in the fratricidal aspirations to the core corporate valuation drivers. It follows their historical development, discusses how they are currently incorporated in valuation processes and identifies the consequences of professionals operating in the future of finance.

From Tangible Assets to Sustainable Value: The Historical Evolution of ESG

From Tangible Assets to Sustainable Value: The Historical Evolution of ESG

During the majority of the 20th century, the corporate valuation was anchored in the physical assets and financial performance indicators. Analysts measured the worth in terms of earnings, cash flows and assets, which can be estimated accurately and quarterly reported. Although this structure worked well in industrialized eras, it did not pay much attention to the externalities such as pollution, labor conditions or integrity of governance, which were perceived as qualitative and reputational risks but not financial.

This changed in the late 1990s and early 2000s with corporate scandals (Enron and WorldCom) and environmental crises starting to surface due to a lack of governance and sustainability. Investors learned that lack of good governance would kill billions of market capitalisation within a short time and that environmental irresponsibility might result in regulation fines and damage to brand. Simultaneously, Globalization and social media enhances scrutiny- companies were no longer allowed to safeguard themselves through financial performance.

The awareness resulted in the emergence of ESG investing, which is a model aimed at introducing Environmental, Social and Governance aspects to investment and valuation analysis. In 2006, the publication of the Principles of Responsible Investment (PRI) by the UN was an important milestone, and it is one that encourages institutional investors to take into account the ESG considerations when making portfolio decisions. Very quickly, reporting frameworks like the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) and Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) and Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) offered systematic methods of measuring and reporting on sustainability performance.

At the beginning, ESG metrics were perceived as additional, as convenient, but not necessary. Nevertheless, the financial community slowly realized that ESG performance is related to long-term value creation, resiliency and reduced exposure to risks. By the 2010s, the major investment firms, including BlackRock, State Street, and Norges Bank, started to state that the ESG performance is explicitly tied to investment decisions.

This was a new dawn: sustainability had gained a new name of sound management and reduction of risks. Due to this, the impact of ESG and sustainability trends on corporate valuation methods started to grow rapidly, shifting the definition of what makes a company valuable in the modern economy..

Understanding the ESG Components and Their Valuation Impact

To understand how ESG factors influence the changing landscape of business valuation, one must first break down what each component represents—and how it affects value drivers.

Environmental (E): Measuring Resource Efficiency and Climate Risk

Environmental factors include the influence of a company on the natural ecosystems- its energy use, waste disposal, emissions, and climate stability. As far as valuation is concerned, environmental risks have direct impacts on operating costs, the regulatory exposure, and the sustainability of the business in the long term.

An example is a manufacturing firm that emits a lot of carbon but will have to pay him/her taxes on carbon in the future or he/she purchase an expensive technology to comply with the standards. In contrast, a company investing in renewable energies or circular production systems can benefit through cost-saving, improved brand presence, and even special conditions of financing by banks or green investors.

Social (S): The Human and Community Dimension

Social factors are associated with the way companies handle the relationships with employees, customers and communities. The problems, including labor practices, diversity, supply chain ethics, and product safety, have turned out to have a significant impact on the performance and reputation.

An organization with a good employee engagement and reputation amongst the community is more likely to record greater productivity, reduced turnover, and an increase in customer loyalty which translates to a stable or increasing revenues. Conversely, lack of a good social governance (like labour tussles or human rights scandals) might result in the loss of brand image, business upsets, and even legal action.

Governance (G): Leadership, Ethics, and Transparency

Governance is a term used to refer to the corporate structures of leadership, integrity of decisions and transparency. Good governance will also see to it that companies act responsibly and in the best interest of the shareholder and stakeholders. Value can be ruined rapidly by weak governance through inviting fraud, mismanagement or regulatory reaction as observed in different corporate scandals.

Governance quality has an impact on investor confidence in a valuation aspect which directly affects the cost of capital of a company. Firms that are well governed tend to receive a lower risk premium and a higher valuation multiple as they are viewed as being more stable and reliable.

Collectively, the three pillars are used to form a complete image of sustainability and resilience of a company. They are now imperative in measuring intangible resources like brand image, innovation potential and stakeholder confidence which were not earlier considered by conventional valuation models.

Integrating ESG into Valuation Methodologies

Although the relevance of ESG is not debatable, its integration into valuation models is a more complicated procedure. The modern day valuation analysts are trained to measure ESG effects that are analogous to known principles of finance, particularly in Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) models, Cost of Capital, and Market Multiples models.

1. Adjusting Cash Flows for ESG Risks and Opportunities

Projections of future cash flows are based on the projection of expected earnings and expenditure through the use of DCF model. These assumptions are affected by ESG factors because they present risks (carbon pricing, supply chain instability, etc.), opportunities (energy efficiency, sustainable product innovation, etc.).

An example is that a firm that makes investments in sustainable technologies can have greater short-term expenses but greater long-term savings and revenue growth due to the difference in the market and regulatory benefits. Scenario analysis is a growing part of cash flow projections undertaken by analysts to test the impact of climate policy or social trends on cash flows.

2. Modifying the Cost of Capital

Investors reward companies that operate effectively in controlling ESG risks by providing them with easier access to funding and reduced cost of borrowing. Consequently, analysts can change the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) to capture diminished perceived risk on high ESG performers-and increased risk premium on laggards.

Studies indicate that companies with strong ESGs have lower volatility, increased investor confidence, and better credit rating that promotes increase in valuation multiples.

3. Using ESG Ratings and Peer Comparisons

The agencies, including MSCI, Sustainalytics, or Refinitiv, are the sources of the ESG rating that give quantitative indicators of positioning companies in industries. These ratings are often used in the relative valuation models, which enable analysts to get the idea of whether a company should have a premium or discount relative to the other firms.

Nevertheless, the problem is that some inconsistency between the ESG rating approaches can result in variations in the ratings of the same company. In the case of valuation professionals, it is important to have an idea of the underlying criteria of each rating system.

4. Integrating Sustainability Disclosures

Valuation drivers have also become a quality of disclosure. Reporting transparently in accordance with such frameworks as GRI or TCFD increases the credibility and reduces information asymmetry. There is a growing trend among analysts and investors to regard good ESG reporting as a sign of sound management and vision, which is worth premium valuation.

Concisely, the concept of valuation integration with ESG is no longer a theoretical game; it is now a common practice in value analysis in the industry and particularly in the fields of finance, real estate, and manufacturing.

ESG, Market Perception, and the New Definition of Value

With the trend towards ESG considerations, the market has started to reward those companies that are showing authentic sustainability performance. ESG and the valuation are not associated with the ethical issue only, it is the matter of financial competitiveness and survival in unstable markets.

1. Investor Sentiment and Market Premiums

The institutional investors are investing a lot of capital in ESG-based funds which have performed better in various regions compared to conventional portfolios. This flow of capital to sustainability gives the companies that have good ESG credentials premium valuation. This may be in the form of increased share prices, reduced volatility, and increased long-term shareholder loyalty, in the case of public companies.

2. Reputation, Talent, and Customer Loyalty

Intangible drivers that are affected by ESG include reputation and acquisition of talent. As consumers and employees, millennials and Gen z are more interested in social and environmental responsibility brands. When a company is sustainably aligned it is able to draw in and keep a superior talent pool, keep its client base loyal and gain a more powerful market presence, which all lead to increased valuation in the long-run.

3. Regulatory and Strategic Imperatives

The regulators and governments are increasing the requirements of the ESG disclosure especially in Europe and Asia. Sustainability reporting is becoming a mandatory requirement of thousands of companies under the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) of the EU and the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB).

The result of this convergence in regulation is that ESG performance will become more and more significant in terms of investor decision and benchmarks of valuation. Companies that change sooner than others do not just abide by rules, but have a competitive advantage provided by transparency and vision.

4. The Risk of Greenwashing

Nonetheless, not everyone has ESG claims that can be translated into actual value. The so-called greenwashing (or the process of overestimating sustainability work) may backfire. ESG disclosures are now reviewed by both investors and regulators on accuracy and materiality. To the valuation professionals, authenticity of ESG information has gained significance as financial statements.

In this way, the new definition of corporate value balances profitability with purpose, transparency and long-term stewardship.

Challenges and the Road Ahead

ESG integration in valuation is developing even though it is getting more accepted. Measurement, standardization, and data consistency are still of major concern.

- Data Reliability: ESG data tends to be self-reported and will be of different levels in terms of depth and accuracy.

- Absence of Standardization: Various ESG rating agencies and platforms cause disparity in scoring and misunderstanding among the investors.

- Sector Variability: ESG is less relevant across all sectors, with environmental metrics being more in the energy or manufacturing industry, and social and governance issues being more in the finance or tech industries.

- Short-Term Market Forces: There are still investors who are obsessed with short-term returns rather than long-term gains that come with sustainability and, therefore, it is hard to get companies to maximize on ESG-based value creation.

With that said, data quality and comparability are slowly enhancing due to the advances in AI-based analytics, blockchain-transparency tools, and built-in reporting frameworks. The second step in ESG valuation can be the so-called impact valuation, which would measure not only the financial performance of companies, but also the impact of their activities on society and the environment in potentially outcomes quantifiable economic terms.

Knowledge of these tools and frameworks will be a career determinant to those professionals joining the field of finance, accounting, or sustainability.

Conclusion

The development of ESG in corporate valuation is one of the most important shifts in the paradigms of contemporary finance. What started as a collection of moral deliberations has evolved to become a fundamental guideline on determining the resilience of businesses, their competitiveness and profitability in the long run.

Currently, the development of the ESG principles of contemporary company valuation highlights the fact that sustainability does not simply mean doing good; it is doing well in the world of high changes. The effects of the ESG and sustainability trends on corporate valuation strategies show that the corporations that adopt transparency, innovation, and ethical leadership are always well-paid with high investor confidence and market premiums. And as we keep on observing the impact of the ESG factors on the evolving business valuation landscape, it is obvious that the future financial leaders will be those that can achieve a balance between purpose and performance.

To junior or middle-level professionals who seek to work in the field of corporate finance, investment analysis, or sustainability, it is not just an ability to master ESG-driven valuation, but rather a ticket to the future of business. Individuals who can comprehend financial statements and sustainability reports will be the first to enter a new more responsible age of international finance.